In Paris, he is seen as a superstar and his concerts are sold out. Măcelaru is the Music Director of the Orchestre National de France and is Chief Conductor of the Köln Symphony Orchestra. He is the 3rd Romanian to win a Grammy Award, he is only 43 years old, and already has an impressive career.

Although he has not lived in Romania since he was 17, Cristian Măcelaru returns to his native country every time he has the chance, passes his knowledge and love for music to the young generation, brings his family to discover its roots and dreams of a better future for Romanians.

As of this year, Măcelaru is also the man who leads the destiny of the George Enescu International Festival, at least from an artistic point of view. He accepted, as Artistic Director of the Festival, a six-year term for 3 editions (2023, 2025, and 2027) and wants to bring people closer to the beauty of music and culture.

Among the concerts that he conducted during the Festival and those in Paris, he takes every opportunity to be a simple spectator. He can be seen in the concert halls alone or together with his family.

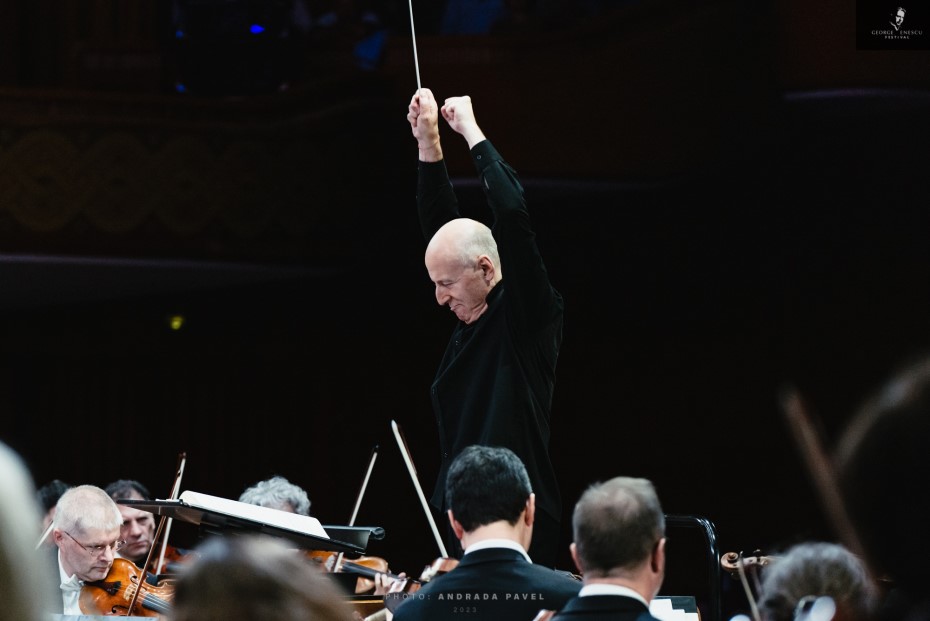

Cristian Măcelaru speaks with warmth and hope about art and the joy he lives through music is seen and felt when he conducts. His joy, is, in fact, contagious.

„It is very important to realize that music alone is not what changes people. Music is the one that brings us together, we are the ones who decide what we do with that gathering.”

Cristian Măcelaru

Two years after the interview in Paris, I met him in the heart of the George Enescu Festival, at the Romanian Athenaeum. In the interview below, he talks about the decisions behind the event, the feelings during concerts, the relationship with music, the norms of society, and, most importantly, about the universe in which we all should bring ideas, information and hope for our children.

***

This year you are the Artistic Director of the George Enescu Festival, conductor and also part of the audience, I`ve seen you many times in the concert hall. When do you feel the biggest emotions?

I can honestly say, I don’t have emotions at all. First of all, as a conductor, I have no emotions because I know the quality of the artistic product that the musicians in the orchestra bring, and I am full of energy anticipating and knowing how the audience will react.

It is not emotion, it is a positive energy that wakes me up each morning because I can’t wait to get to the concert.

Then, as a spectator, I’m very happy. In fact, this is the first time I can attend several events as a spectator. I’ve been to the festival as part of the audience before, but I’ve attended one or two concerts.

Now I feel like a kid in a candy store because I choose any concert I want to see, and I meet many musicians I work with. It`s like we`re at a friendly reunion singing to each other.

And that’s just a small side of the festival, actually. These artists who come here intersect with each other and this is how beautiful ideas in art are born.

As an artistic director, I have emotions in the sense that I want to completely reach the end, as I planned, without too many barriers. When you have 3,500 artists from all over the world traveling to the festival, of course, there are problems that arise. There are things we need to rearrange every hour and every day.

By the time you took over this term, in what proportion were the artists contracted and the musical program arranged?

When I took over as artistic director, I can’t say there was anything confirmed. There were a few things in discussion, natural things, even now we have talks for 2025 and 2027, because great orchestras plan 5-6 years ahead, and I do the same.

And then, there were discussions all the time, but everything was confirmed after I took over.

In terms of the program, does each orchestra choose its repertoire, or does the festival impose what is played, so that there is general coherence in the event for a month?

First of all, let’s think about the history of the festival. In 1958 it’s purpose was to promote Enescu’s music. This was the term of the festival. Since then, it has continued to promote Enescu’s music, but in a more global context.

This year, in the festival, 39 compositions of Enescu are presented and we continue this effort. That’s why we negotiate with all the orchestras that come.

Many orchestras are on a tour of their own, and at the festival, they stop for one or two days.

It is impossible to impose a different repertoire on each orchestra, it is negotiated. But all the orchestras that come to the festival know in advance that they have to interpret a work by Enescu.

When the orchestras come to the negotiation, they ask „which work of Enescu is not already taken?” For example, I proposed to the Vienna Philarmonic to perform one of Enescu’s suites, and they accepted, then they realized that there was not enough time for rehearsal of the Suite in Romania. And then they integrated Suite No.1 of Enescu, a 30-minute work, in their entire tour.

I was at the Graffenegg Festival in Vienna and the Vienna Philharmonic played Enescu’s Suite. And this made me so happy because our effort to make the composer George Enescu known to the whole world is beginning to catch strong roots.

Beyond Enescu`s music, did you have any preferences for certain works or composers that you wanted to promote in the program?

Of course. First of all, it is the anniversary year of György Ligeti, a composer born on the Romanian territory, highly appreciated especially in the 20th century, when he lived. That’s why Ligeti’s music has a special role in the festival.

Then, I really want to promote Bartók’s music, because he is another composer that many are afraid to listen to because they don’t know what will discover.

Bartók has long been considered an extraordinary modernist, but I find in his music such a deep and beautiful romance! Even when he is very modern, still he has such a profound element. It’s like when we look in Romanian folklore and see these extraordinary masks, then something like the Merry Cemetery, all the fantastic things. This is Bartók’s music and must be understood in this context.

I promote Bartók’s music everywhere because it speaks so deeply about the culture I come from.

He was born in Sânnicolau Mare, I was born in Timișoara, 20 or so kilometres away, his music comes from the same land I come from. I identify very much with the gestures that Bartók writes in music, that’s why his music is promoted in the festival.

As an audience member, have you been particularly impressed by any concert?

I can say that all of them impress me, because I don’t listen to music in a comparative way, looking for the superlative, but I am interested in the person-person relationship. Music is the language through which artists communicate. But that relationship, human to human, is actually the beautiful thing in art.

Art is such a personal thing that there can’t be a climax that makes you lesser if you don’t reach it.

And then, is each person’s experience during the concert the most important?

Exactly.

And what you bring defines a lot of the success of the concert, not just what the artist brings. The artist always brings something of his own, something personal. But what I bring, so that we can connect in the concert, that’s what the success of the concert depends a lot on.

I can say, from my memories of the last few days, that to see Maestro Zubin Mehta conducting an entire opera at the age of 90, without once looking at the score, doing everything with technical perfection from a conducting point of view, is simply a miracle.

Likewise, Mahler’s 9th Symphony, with Sir Simon Rattle and the London Symphony, was of such beauty and deep feeling! Especially knowing that this is the last time they will play with him as the ensemble’s conductor, there are elements beyond the music that make the concert very special.

It was also quite special what happened at the Tonhalle Orchestra concert in Zurich at the Palace Hall, when despite the Ro Alert alarms, the artists continued to play in an extraordinary way and be above those moments. And at the end, the audience applauded for minutes on end to Dvořák’s 9th Symphony.

Right. I was there. The audience also wanted to show their appreciation for the fact that the artists didn’t stop the concert.

I talked to the orchestra after the concert and they said “unfortunately, we also saw the Ro Alert at half-time, but because it was in Romanian, we didn’t understand what it was and, being in proximity to the war in Ukraine, we didn’t know what was going on, is it a fire alarm, has Romania been invaded?”.

Of course, after the concert, we talked internally to establish a more defined protocol, to let people know how to turn that phone off, so they would stop calling.

It’s to be applauded how the artists reacted to those sounds.

I saw that during the break you went to congratulate Andrei Ioniță. What did you say to him?

Of course, I played with Andrei, he is very appreciated in Romania, he is our hero, a special and extraordinary talent, with a lightness on the instrument that is appreciated by those who know how difficult it is to play the cello. They really know what a talent Andrei is. He is a very great talent and I told him exactly that.

You and your family went to a few concerts. How do the kids feel about the festival?

They love it. Unfortunately, because they started school in Paris, they couldn’t stay to see more of the festival. They like it very much in Romania, they have their favorite places to go, playgrounds or Cărturești, they go there since they were very young.

I also try to teach them a little how to listen, what to look for and I enjoy it when they ask me questions. In Germany, when I did The Woodcarved Prince, I did it with the subtitles of the story. It’s a ballet with a story behind it, in which Bartók wrote the music in such a way that Wagner did in his operas. There are musical brassy motifs that coincide with certain important words in the story.

And when the children came here, they were afraid that without subtitles they wouldn’t understand the story. And we made a video where we explained those musical motifs for them to recognize, we watched the video together, told them the story one more time and that’s how they came to the concert.

It is very necessary that parents who bring their children to the concert take 5-10 minutes beforehand, I make this effort like any parent. Depending on how you introduce the kids to the concert, to a work, their experience will be very different.

That’s what interests me most, that people discover the same beauty at the concert that I do.

A little knowledge helps you understand music and listen to it differently, so you’ll have a deeper, more beautiful perspective.

In fact, for me, that’s the difference between art and entertainment. In art you have to bring something of yourself to discover beauty. In entertainment you don’t need anything at all except a ticket.

In art, the more you bring in, the wider the universe you discover.

When you took over as artistic director, you said that you wanted very much to open the Enescu Festival to children and young audiences. You have included in the programme a series, for the first time, for children, which is sold out. Do you feel you have achieved what you set out to do?

It’s a successful first step, I say. I will continue to do more in this direction. Maybe some people say “ah, what a good idea, so that in 20-30 years we have a new generation coming to the festival”. Yes, that’s true, but my main interest is that these children and young people who come to the concerts discover culture, discover their relationship with art.

You don’t learn culture from a textbook in school. You don’t learn it by reading about it. Culture is absorbed when you don’t realize you’re absorbing culture. Culture takes time and effort, not just personal effort.

We must provide possibilities and opportunities for these children of ours to be exposed to culture and art. There is a space in society, a universe that is filling up with information, with ideas. If we don’t put ideas and information into that space, someone else will gladly do it.

We need to fill the universe with something good, from which children take what they want. The moment we have a presence in that space, maybe they will take culture.

To what extent do you think art should be related to what is happening in society? It was moving when you dedicated the Second Rhapsody to the victims of the Crevedia explosion and linked the work to the idea of healing. It took on a new meaning.

Music has always been, in fact, the thing that has accompanied everything we have done as humans. The beginning of organized music was to bring people together. Whether it was at a funeral, whether it was at a wedding, whether it was at a natural phenomenon, music has always had that purpose, to bring people together. Then, we are the ones who give the purpose of our gathering.

It’s very important to realize that music alone is not what transforms people. It’s the music that brings us together, it’s we who decide what we do with that gathering. Because there is so much power in 2000-3000 people coming together and listening to the same thing. There is a spiritual power in the universe.

And what we do with that power in the universe can lead to good or it can lead to evil.

It is important to reintroduce music as a catalyst for good. The idea of healing through music is as old as the universe. We need that soul-soothing.

And music like Enescu’s Second Rhapsody was put in a special context and everyone in the hall heard it in a different way than they had heard it before. One thought of 4000 people towards the same thing transforms a universe.

To what extent does clothing still matter at these events nowadays? There is still the impression, at times, that the Enescu Festival is a stiff event, where you have to go dressed up elegantly. I know that your view is a bit different, in the sense that you don’t consider the attire being a prerequisite for attending such a concert.

Elegance itself is up to each individual. I’ve seen people in jeans who are very elegant, and I’ve seen people in suits who are not elegant.

It’s not the clothing itself that gives a person elegance, but elegance comes from within.

For me it doesn’t matter how people are dressed, but there must be a special feeling, an internal elegance when you are face to face with Enescu, Mahler or Beethoven. There has to be a reverence for these geniuses. Not for musicians, not for conductors, but for composers. For me, the composer is the complete genius.

And when I go to concerts in jeans and when I go in a suit, I bring a reverence through internal elegance, which I think is necessary.

For those who only stop at clothes, that’s their understanding, but I hope they can get away from this idea that you have to be dressed a certain way. Reverence is something that has to come from inside, because if it’s not from inside, it’s a false thing and it’s not good.

At what stage are you with the project you have with the French National Orchestra to record the complete operas of Enescu?

We finished recording the first three symphonies and the two rhapsodies, we spent almost 4 weeks, a lot of work. Next comes studio sound editing. And probably next year the records will come out.

Did you feel that you brought the French National Orchestra closer to Enescu with this project?

Yes. And I would say Enescu closer to the French National Orchestra. I don’t know any musician who hasn’t discovered Enescu’s music, who hasn’t been overwhelmed by the beauty, the extraordinary universe that Enescu offers.

Because he is so complex, Enescu requires more than other composers. That’s why there are so many people who haven’t discovered Enescu yet. They’ve heard him, but they haven’t discovered him.

When and how did you discover Enescu?

I discovered him playing his music. And I’ve been obsessed with his music ever since. Enescu must be studied, discovered and understood

In the interview we did together in Paris two years ago, you talked about how important a concert hall would be for Romania. Has there been any progress in discussions with the Romanian authorities on this matter since you became the festival director?

What I can say is that I still haven’t found a person in the government or outside who disagrees with the idea that we need to do something. Everybody has said “oh, it’s necessary.” For 30 years it’s been necessary. But what we haven’t found is a coalition of all the people who need to make the clear decisions.

We did our part, Artexim, Mr Mihai Constantinescu who has been fighting for this for 30 years. They have made a project, but it is not green lit until the end.

Honestly, I can’t even say that there’s a specific person who hasn’t given his consent. No.

It’s such a volatile system, it changes so often, it’s kind of absurd. A project of this magnitude needs continuity. A concert hall can be built in 2-3 years.

But why do you think it doesn’t happen? What is missing?

In my experience, people who have been persuaded and want to do this simply change their position. And then you have to start over with the next guy. The battle has to start from scratch.

I think since you’ve been in talks to take over as director, you have already changed three Ministers of Culture.

Three, that’s right. Not to mention Mr. Mihai Constantinescu, in 33 years he went through about 40 ministers. But it’s not just about ministers, it’s about a system.

A train conductor, no matter how much he wants to go forward, if every person and every screw in that train is not put in the right place, the train will not leave the station.